Centre For Local Research into Public Space (CELOS)

Playground injuries bibliography file (1)

Quick Page Table of Contents

Scanning...

See also the quick points page

Playground injuries leading to at least 1 night of hospital stay, by the numbers, 1994 to 2014, (CIHI)

2005: The Sick Kids article

Editorial: Globe and Mail, 25 May 2005

SMOKE AND MIRRORS ON PLAYGROUND SAFETY

For a moment yesterday, it seemed as if those who want to keep children in a bubble and deny them any possibility of risk -- those who would take away the humble tire swing from a generation of fragile littl'uns -- were in the ascendant. Vindication, cried the trustees of the Toronto District School Board and all who share their vision of risk-free, fun-free childhood.

Five years ago, the board ripped out the playground equipment at more than 100 elementary schools because it did not meet the letter of tough new safety requirements. The cost of demolition and replacement was $6.3-million, not to mention the unquantifiable loss of beloved play spaces, including the now-verboten tire swings.

Yesterday, a study by Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children, published in the Canadian Medical Asso-Association Journal, suggested it had all been worth it. "New school playgrounds prove safer," said The Globe and Mail's report on the CMAJ study. "Child's play now safer," said the Toronto Star. "Fewer children hurt since monkey bars upgraded: accidents decline 49 per cent: study," said the National Post.

There was only one problem. The study proved nothing of the kind.

It said that, at the 86 schools with replacement equipment reviewed in the study, there were 550 fewer playground injuries in the course of a year. But the vast majority of that reduction, the study showed, occurred not on the playground equipment but elsewhere in the schoolyard.

In fact, there was a reduction of just 117 injuries -- at 86 schools -- on the playground equipment. That amounts to roughly one fewer injury per school per year. And for this, Toronto spent $6.3-million.

So what, you might say. Perhaps it was worth the cost, if one fewer child at each school lost an eye or broke a neck or a back. But the study does not mention the seriousness of injuries on Toronto's playground equipment either before or after it was replaced.

This is no trivial omission. The school board made it clear that its purpose in replacing the equipment was to protect against severe hazards. The board's decision was never about reducing the number of broken arms or twisted ankles or cutting what the CMAJ study dubs "injury rates." It was about preventing death from strangulation (though there hadn't been a recorded case in Toronto) or debilitating head injuries from falls onto unforgiving surfaces. It was about protecting against lasting disability. Yet the authors simply did not have the data to show any such result. The injuries might be more severe now, even if fewer in number, and the authors would not know. All they know is that the injuries required attention, whether from a hospital or simply from a teacher or parent. This is a crucial failing. The study makes no attempt to determine whether the school board achieved its stated goal of reducing severe injuries.

It is not terribly difficult to reduce childhood injuries on playgrounds. Build the equipment ultra-safe and ultra-dull (the children will climb trees instead). Take away the tire swings and there will be no tire-swing njuries. Unless boredom is an injury. Unless missing a chance to develop oneself through play is an injury.

Vindication? Hardly. The seeming victory for this damaging overprotectiveness in child-rearing turns out to be more finger-wagging and hot air.

There was no response to this editorial and the article has continued to be widely quoted as fact ever since.

Safe Kids Canada, 2007

Safe Kids Canada: 10 years in review, 1994 - 2003 Child & Youth Unintentional Injury

As one example, changes to playground safety standards may be having an impact; a research study into school playgrounds in Toronto upgraded to the new standards concluded that approximately 520 injuries had been prevented over the 4-year study period. [Footnotes 6, 161, 169: Howard A, Macarthur C, Willan A, Rothman L, Moses-McKeag A, MacPherson A. “The Effect of Safer Play Equipment on Playground Injury Rates Among School Children.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 2005; 172(11):1443-1446.]

The Canadian Standards Association (CSA) developed the nationally recognized standard for children’s play spaces and equipment. This standard specifies numerous design and maintenance criteria to reduce the risk and severity of injury, such as hand rails and barriers and a deep, soft surface under equipment. Appropriate surfacing can reduce the severity of the injury compared to a fall on a harder surface.

Footnotes 159, 160: Recent research by The Hospital for Sick Children showed that school playgrounds in Toronto that had been upgraded to the CSA standard had a 49% decrease in injuries compared to schools whose playground equipment had not been upgraded. The researchers concluded that an estimated 520 injuries may have been prevented during the 4-year study period.

Centre for Justice and Democracy: White Paper, August 2006. Amy Widman, Attorney/Policy Analyst:

Recently, some corporate-funded “tort reform” groups have seized on children’s playgrounds as a new area to exploit to further their “tort reform” agenda. Misquoting child psychologists and manipulating data on lawsuits, these groups publish op-eds and articles arguing topsy-turvy notions like safe playgrounds are bad for our children....

.....In 2005, the American Academy of Pediatricians journal Grand Rounds published an article about the importance of improving safety standards to reduce playground injury rates. This article examined a Canadian study comparing injuries at playgrounds that followed new Canadian safety standards against playgrounds that did not. The researchers replaced dangerous or defective playground equipment and removed environmental hazards (poor drainage, hard surfaces, etc.) in the 136 playgrounds that fell under the new safety violations and found that such intervention reduced injuries by almost half.

Toronto Star article, July 19, 2007

- about increased playground safety, quoting CIHI data.

Safer playground equipment and softer surfaces have helped drastically reduce the amount of serious head injuries to children, a new report from the Canadian Institute for Health Information shows......Hospital admissions for head injuries have declined dramatically. In 2002-2003, head injuries accounted for one in five admissions to hospital. That number is now 1 in 15, the CIHI report shows. The chief reason for the decline seems to be improved playgrounds, said Margaret Keresteci, manager of clinical registries at CIHI.

"Because most of these injuries happen during falls, falling onto a concrete surface and height of the equipment is an issue," she said. "It seems quite likely that the investment we put into really thinking about our playgrounds and designing them appropriately is paying off."

....Modern equipment that upholds safety standards means fewer serious head injuries, agreed Dr. Andrew Howard, an orthopedic surgeon and medical director of the trauma program at the Hospital for Sick Children. But other playground injuries can still be severe.

"If you send school-aged children to play on a grassy field, you'll get an occasional broken arm," he said. "On the playground with equipment present, there is a four times higher risk of having a severe kind of fracture compared with a low-energy normal fracture of childhood."

April 1, 2015, Mariana Brussoni, Ian Pike and Alison McPherson: Can we go too far when it comes to children's injury prevention?:

Head injuries on the playground are extremely rare and there is no evidence that they are increasing on playgrounds. For example, studies that have looked at injuries across entire school districts in Canada and New Zealand have not documented even one head injury on the playground. In fact, your child is more likely to get injured doing sports than on the playground.

The head injury criterion (HIC) is measured by dropping a head form straight down, but children do not fall that way. The most common injuries on the playground are arm fractures because children try to break their falls. Australian data show that introducing stricter playground safety standards in 1996 had no impact on head injury rates.

“Preventing playground injuries”

Paediatr Child Health 2012;17(6):328 (wrong link) Principal author(s) P Fuselli; NL Yanchar; Canadian Paediatric Society, Injury Prevention Committee

From 1994 to 2003, an estimated 2500 children ≤14 of age were hospitalized every year in Canada for serious injuries from playground falls. Approximately 81% of these children had a fracture, while 14% were hospitalized for a head injury; the remaining 5% had injuries such as joint dislocations and open wounds. Over the period studied, hospitalization rates declined by 27%, likely in response to improvements to playground equipment and compliance with playground safety standards [8].

…..Changes and enhancements to the current standard included a lower optimum fall height measurement, a surfacing materials comparison chart and additional guidelines for making play spaces more accessible to children with special needs [18]. One study has shown that playgrounds modified to meet the current CSA standard can reduce associated injuries by as much as 49% [13]

Jan 21, 2-14, on RestoreCSA.com: "Standards for Sale":

RestoreCSA recently commented that CSA members are paying to have regulations developed to their liking which they may then leverage to their commercial advantage.... In 1990, the CSA had a small footprint in playground regulations, they were called “guidelines” back then. In 1997, the CSA was working on a new set of playground standards and the committee they struck for the purpose included most of the country’s playground manufacturers. But there were no worries about conflict of interest because the texts they were drafting were voluntary, they were just “guidelines.” In 1998 however, once the new texts were ready, the CSA rebadged their voluntary guidelines as “standards.” The City of Toronto then sent staff to CSA standards workshops where they learned that existing City playgrounds were “not compliant.” Staff were referencing the “requirement to make the play equipment compliant with the new standards” and the need to remove “CSA infractions.” By 2000, government agencies were being advised “to be familiar with and comply with” the new CSA standard. Municipalities by then regarded CSA as a “lawmaker.”

Note the language. It took just three years to move from “guidelines” to “standards” and from “voluntary” to “requirement.” But all of these terms refer to the same text....

ASTM

Jay Beckwith, "the road to hell is paved with good intentions" Feb.19, 2015

-- writing about the ASTM:

...we do know the ASTM process, and it is deeply flawed.... It is quite clear that the whole process used in the creation of the surfacing standard is not based on robust science. For example, there has never been a formal A/B test where the same equipment and populations used different levels of fall attenuating surfacing. I can say that my experience in those cases where wood fiber was replaced by rubber mats, the incident of broken arms went from zero to several times a month. This got to be such a known risk factor that in many cases the wood fiber was reinstalled over the mats.

The industry is quite candid in their acceptance of this situation. They know that mats produce more long bone injuries than wood fiber....

….how can we expect a system, in which every person in the decision-making process has a profound conflict of interest, to arrive at the overall best solution for society? How can we expect a process which is populated exclusively by engineers and business owners, and which systematically excludes broader representation, to understand that not every problem can be solved by the only tool they have.

I say it’s time we take a pause. It is time we demand that there be a broader range of experience, expertise, and opinion brought to bear on the issue. And it is time that we require actual proof that the proposed increase in the standard will actually produce the intended improvements to children’s safety.

Playground standards

David Ball blog (Thoughts on Risk and Public Safety), Dec.25, 2014

....Standards on play safety have colonised areas of decision making which should be the domain of local play providers who know what their local communities need and want.....Secondly, it will be apparent that many playgrounds have come to resemble factory environments laden as they are with their metal stairways, evenly-spaced steps, handrails and crash barriers, and rubber surfaces...more

Letter from Robin Sutcliffe of the Play Safety Forum July 2016.

To the British Standards committee:

I am writing on behalf of the UK Play Safety Forum to express our deep concern about the proposed amendments to EN 1176 specifically in relation to the requirement for site testing of impact absorbing surfaces. The forum believe that the case for surfacing itself is controversial and that the level of serious injuries sustained from impacts resulting from falls within playgrounds is not significant and could therefore not be significantly reduced by this measure. The increased costs will either reduce levels of investment in play or see policies of play spaces being removed, or, more probably, both. It therefore follows that if this measure is implemented it will have a serious impact on the wellbeing of children across Europe.

Bernard Spiegal blog, August 25,2015:

I have stressed previously that playground equipment and surfacing Standards are a civil society matter not to be determined by committees heavily weighted in favour of special interests and seemingly dominated by a medical-cum-engineering value orientation. Having said that, one can begin to detect a stirring of civil society interest in, and a preparedness to take action on, Standards.

At present, discussions about play equipment and surfacing Standards are conducted on the terms set by Standard-making bodies, in this particular case, the ASTM. One can’t help but believe that this court is rigged in favour of sustaining its assumed exclusive right to generate stipulations that too often weigh heavily on play provision, with questionable benefit. This is not to say that Standards have no role to play – they do. But current structures and processes for formulating them are fundamentally flawed.

Given that so many jurisdictions make Standards mandatory, and others treat them as though they were, we are in fact dealing with a publicly unaccountable body that affects public policy – and public expenditure – in a profound and disturbing way. It is not a minor matter. Still less merely a technical one.

Spiegel tells about a BC case that rejects a lawsuit for letting kids play grounders in a playground during day camp:

the District’s duty to the plaintiff did not include the removal of every possible danger that might arise while she was in the care of its employees, but was only to protect her from unreasonable risk of harm.

Bernard Spiegal blog, July 1, 2016:

A UK, Europe and world-wide matter

I have stressed before that play equipment and surfacing standards are an international matter. What starts or is agreed in one jurisdiction, pretty quickly spreads to others. This is in because Standards are one expression of a pro-free trade ideology. Whether that ideology is right or wrong, one intent of Standard-making is directed at their international harmonisation in order to facilitate trade between nations and trading blocs. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) negotiations are part of this too and, as suggested in a previous piece, if implemented could potentially further hamstring and pile on the costs for those responsible for play provision.

Tim Gill blog, May 17, 2017, on this injury article:

The study used data from a national injury surveillance system to work out injury rates for each year between 2001 and 2013. It also looked at whether or not children were admitted to hospital and the playground equipment involved, amongst other factors, and it analysed the data for trends. It claims to be the first national study on playground-related TBIs since 1999.

The study is important not only because of its new data, but also because it has led to widespread media coverage in the USA. Moreover, it has been widely discussed within the playground safety community. I understand that it has been circulated to members of one of ASTM’s playground safety committees by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Members tell me that it is being seen by some as providing evidence for reviving the playground surfacing proposal that ASTM ultimately rejected last year.

The study found an average of around 35 ED visits per 100,000 children under the age of 14 per year over the 13-year period. The figure was higher for children aged 5 – 9 years (53.5 per 100,000 per year). The study found that on average, 2.6% of the children visiting ED were admitted to hospital: a rate of 0.9 children per 100,000 per year. This suggests that the vast majority of playground-related TBIs would – to quote the paper – “likely be best categorised as mild in severity.” (Clinicians typically categorise TBIs as either mild, moderate or severe, depending on the presenting symptoms.)….

The figures show that an average American elementary (primary) school of 500 pupils would expect to see around one ED visit from a playground-related TBI every 5 or 6 years. As already noted, the figures for hospitalization were much lower. They mean that a city with a total population of around 700,000 – about the size of Memphis, Tennessee – would expect to see one hospital admission each year due to a playground-related TBI.

Apart from looking at whether or not they were admitted, the study itself did not follow up what happened to the injured children.

The paper states that “TBIs, even those categorised as ‘mild’ can have serious implications”. The study itself does not provide new evidence for this (as already noted, there was no follow-up data). The paper cites four other papers in support. However, this supporting evidence is not strong. Two of the studies cited do not look at mild TBIs, so they cannot support this claim. A third study found a strong association between severity of TBI and outcome (the more severe the TBI, the worse the outcome). The final study cited did find evidence of adverse outcomes for mild TBIs. However, the study’s authors note that this may have been because of pre-existing conditions and not a result of the TBI itself (the study design ruled out claims about cause and effect).

From Tim Gill's blog May 15, 2015:

How many Canadian children die in playground accidents? An open question to Rolf Huber

I am openly addressing the question to Rolf Huber, for two reasons. First, because he is a longstanding member of the relevant ASTM committee, is well-known in the playground industry for his leading role in the standards-setting process, and has made public statements in favour of the ASTM change. Second, because he came along to my talk last night at Metro Hall in Toronto, and disputed my answer to this question.

What is my answer to this question? My answer is zero. That is right. Zero. According to Dr Mariana Brussoni of the BC Injury Prevention and Research Unit, who I met in Vancouver a couple of weeks ago, there have been no such fatalities for at least the last 20 years. [Update 16 May 2015: it looks like the answer is that there were two such fatalities over the 30-year period 1982-2011 – see Mariana’s second comment below.]

….What is Rolf Huber’s answer to this question? At last night’s Toronto meeting, Rolf claimed that 20 children in Canada had died on playgrounds as a result of equipment-related injuries over the last 20 years. The gulf between his answer and mine (via Mariana) is huge: I must say I was very surprised to hear his figure. I know that some people are wary of statistics, especially on such an emotive and distressing topic. But statistics are vital in gaining a sense of the scale of the problem. And while statistics can be collected, interpreted, debated and abused, they cannot and should not be ignored.

Ken Kutska, chair of the ASTM playground subcommittee about a World Playground Standard:

On September 8, 2004, international playground safety consultant Monty L. Christiansen (today retired Professor Emeritus, Penn State University), presented the keynote address to the Japan Playground Facilities Association (JPFA) National Playground Safety Conference entitled “International Playground Safety Standards − An ASTM International Case Study: The American Experience in Retrospect: Best Intentions Gone Awry”. The conclusions presented by Professor Christiansen thirteen years ago are still very relevant today to all playground standards writing organizations. This paper revisits these points and enlarges them in perspective of the international situation today. Public playground safety standard stakeholders convening in Canada on November 20 – 22, 2017 will be discussing the possibility and need for a worldwide safety standard for playgrounds and equipment....

....The formation of IPSI came about as a result of very successful 1995 and 1999 International Conferences on Playground Safety held at the Penn Stater Conference Center, University Park, Pennsylvania, both conferences chaired by Monty. Selected portions of the proceedings of these conferences are being reprinted and distributed to prepare participants for the November 2017 Toronto Conference: Harmonizing Opportunities Towards a World Playground Standard....

....The need for playground safety standards in the United States arose as a result of several serious injuries and fatalities that occurred during a relatively short time period in the last 30 to 40 years. These injuries were sensationalized through local and national print and broadcast media. It was a perfect storm brought about by the need for more public playgrounds, the media’s interest in some of the more serious injuries, and rising number of litigations filed demanding compensation for recovery of injury costs and punitive damages. Several huge financial awards consequently led to a strong public demand for increased safety. Many well minded individuals and organizations believed the problem of playground injuries was “solvable.” They believed the problem of rising frequency of serious playground injuries could be resolved through the development and compliance to safety standards based upon facts learned through the collection and analysis of injury data....

....Today standards writing organizations have come to realize that prescriptive use standards for the design of playgrounds and playground equipment is a waste of time and effort. These organizations are no more able to keep up with innovation in play apparatus design than they are able to limit its usage to intended design use.

Stories from Canada

Ken Kutska's idea that the playground standards campaign was innocently well-intentioned is not borne out by the Canadian experience. There were many commercial and turf interests at play from the beginning, as can be seen from this excerpt from a book in preparation:

So the Frank Cowan Insurance Co., and many other municipal insurers, got busy trying to fix up what they called “the play environment.” The Cowan newsletter deplored to the absence of binding regulations to protect municipalities against lawsuits (and insurance companies against pay-outs): “If the goals and objectives [i.e.safety from claims payouts; ed. note] are to be achieved, those who contribute to the play environment must be obligated to its recommendations.” In the meantime, the newsletter drew attention to the 1990 manufacturers’ guidelines of the Canadian Standards Association, and urged their municipal clients to set up an inspection program based on those guidelines, for the present. They recommended three reputable sources to help set up a playground inspection program: “Your insurance carrier, a well-established playground manufacturer, or one of the many recreation related associations.” Advice taken: as it turned out, those would be the three main players in setting the stage for an epic of playground destruction whose cost would far outstrip any insurance settlements for injuries. more

CSA

Notes from CELOS researcher Belinda Cole’s meeting with Professor Susan Herrington - September 12, 2008

"I asked Susan if she had had any response to the article Outdoor play spaces in Canada: The safety dance of standards as policy that she co-wrote with Jamie Nicholls, and which was published in the journal Critical Social Policy. She told me a very interesting story about what happened after the article was published in 2007. In May 2007, the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) contacted the two Directors of the School of Architecture under whose direction Susan works as an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia, and the President and CEO of Sage Publishing, to challenge what they said were several misconceptions and false allegations presented in Susan and Jamie's article. The author of the letter, Anthony Toderian, Senior Media Relations Officer of the CSA Group, insisted that Sage Publications:

1. take immediate action to remove this publication from your [its]website; and

2. issue a public retraction with respect to the publication of this article, which will have the same prominence and distribution as the original article.

CSA representatives also contacted university colleagues of Susan's to discuss their concerns about the article. No one from the CSA contacted either Susan nor Jamie to discuss the article before this.

After the letters were sent to their superiors, Susan and Jamie began to receive calls from various CSA representatives and Board members citing the same concerns outlined in the letter. One Board member, who wished to remain anonymous, told Susan that her article was, in fact, true.

Susan and Jamie both consulted with lawyers from the University, and also dealt with the lawyer from Sage publications who reviewed all of the CSA allegations. The outcome of this review was that Sage Publications changed the wording in the article in only one instance, as follows:

the sentence The CSA is also directing the removal and redevelopment of playgrounds at a city-wide scale in Canada. should in fact read The CSA's standards are also being used to direct the removal and redevelopment of playgrounds at a city-wide scale in Canada. The authors of this article apologize for this error and for any confusion it may have caused.

After this, neither Susan nor Jamie heard anything more on the matter from the CSA or their representatives.

Before she and Jamie wrote their article, Susan had been invited to a private CSA Board meeting in Vancouver as the lunchtime speaker to talk about the findings of her research done on play and playground equipment at daycare centres in Vancouver.

The results of this study are published on the host website of Westcoast Childcare Resources, the 7cc's at the lower right hand corner. One of Susan's findings was that the playground equipment built in accordance with the CSA standards was not used 87% of the time."

Playground morbidity data

CBC news on playground injuries

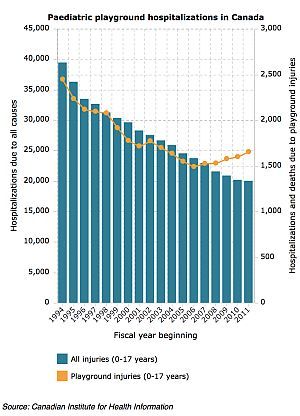

Note that this item shows a graph that suggests CIHI was collecting playground hospitalization data every year between 1994 and 2011. I sent an email to CIHI on March 16 2017 asking if this was the case. (Answer: have to pay to get data)

Note: the playground-related hospitalizations continued to rise to the end of 2014 (the last year CIHI made their data public)

From Chris Selley, National Post Sept.19, 2013

Commenting on the CIHI release:

It’s also a mystery where the 28,000 injuries per year figure comes from. In 2008, the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP), which includes four general and 11 pediatric hospitals, reported just 3,960 playground-related injuries. That’s not a complete sample — but can there really have been seven times more? And 28,000 bears no relation to the 8% rise in hospitalizations mentioned in the same sentence, which was from 1,524 in 2007 to 1,654 in 2011. Those data come from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI)…. the CHIRPP data tells us a lot about the types of playground injuries parents might reasonably prepare for: At the extreme end of the 3,960 reported injuries in 2008 were two amputated fingers and 1,853 fractures — 1,440 to the upper body, 381 to the lower body, 19 to the face or skull, and 13 to the spine or ribs. None of that is any fun, but only a tiny fraction of these would be life-changing events. What parents are most afraid of, presumably, are major injuries, which CIHI tracks in its National Trauma Registry. (“Major injury” is a relative term defined, somewhat circularly, such that 10% of injuries so classified are expected to be fatal.)

For 2010, the CIHI database of major injury hospitalizations contains 1,918 patients under the age of 20. Of those injuries, 387 (20%) were caused by falls. And of those 387 falls, just 12 (3%) involved playground equipment. More menacing circumstances included skating (4%), “slipping, tripping and stumbling” (5%), negotiating stairs (10%) and roller-skating, rollerblading and skateboarding (13%). So playgrounds aren’t a significant source of major injuries even from falls. And overall, we’re talking about something like 0.6% of major childhood injuries.

CELOS article: "Pick a Number, Assign a Cause."

....Making up data by simple multiplication, without telling, is not considered reputable statistical practice. But this numeration was not about careful study of the evidence. It was about getting a number big enough to be a quick-click icon, to be turned into a banner under which playground safety advocates would then march across the land, taking out swings, climbers, slides, and whole playgrounds on their way.

Ibrahimova A, Piedt S & Pike I. (2013)

Playgrounds and Neighbourhood Play Spaces in Canada, Key Informants Survey Report. A report prepared by the BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit for the Public Health Agency of Canada. Vancouver, BC:

An estimated 2,500 children age 14 and younger are hospitalized every year in Canada for serious playground injuries. Of these, 14% are head injuries, 81% are fractures and 5% are other injuries (dislocation, open wound, etc) [9, 10]. Falls from equipment are responsible for 60% to 80% of all medically attended playground injuries [9, 11].

According to Canadian Hospital Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP), there were about four thousand injuries associated with playgrounds in 2008.

Footnote 9. SafeKids Canada. Child & youth unintentional injury: 10 years in review 1994 – 2003.

Footnote 10. Canadian Council on Social Development. The progress of Canada’s children. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Council on Social Development; 2001

Footnote 11. Mott A, Evans R, Rolfe K, Potter D, Kemp KW & Sibert JR. Patterns of injuries to children on public playgrounds. Archives of Disease in Children, 1994, 71: 328–330;

Footnote 12. Injuries associated with playground equipment (PGE) 2008, Ages 0-14 years. CHIRPP Injury Brief.

On their advisory committee – Sally Lockhart (listed first, formerly Health Canada), also Scott Belair CPSI and Pamela Fuselli (Parachute Canada)

Show search options

Show search options

You are on the [Playground Injuries File] page of folder [Playgrounds Notebooks]

You are on the [Playground Injuries File] page of folder [Playgrounds Notebooks] For the cover page of this folder go to the

For the cover page of this folder go to the